Who is the most powerful “wicked witch” ever?

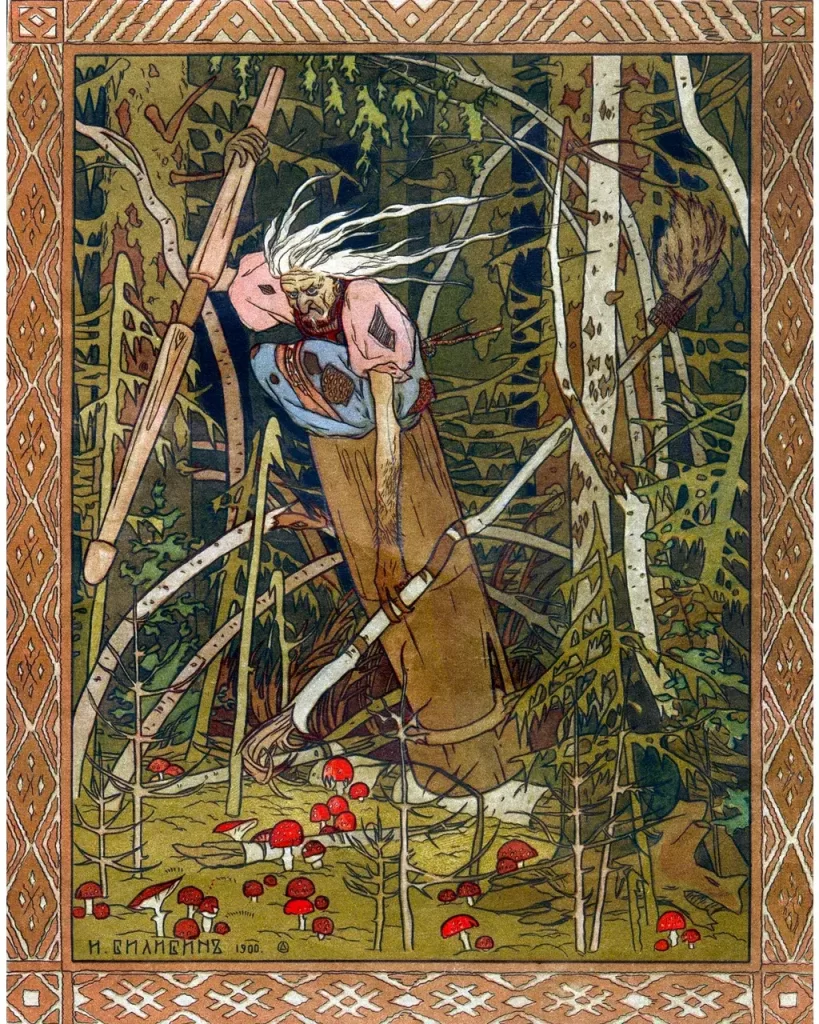

A key figure from Slavic folklore, Baba Yaga certainly fulfils the requirements of the wicked witch – she lives in a house that walks through the forest on chicken legs, and sometimes flies around in a giant mortar and pestle. She usually appears as a hag or crone, and she is known in most witch-like fashion to feast upon children.

However, she is also a far more complex character than that synopsis suggests. Cunning, clever, helpful as much as a hindrance, she could indeed be the most feminist character in folklore.

The Baba Yaga legend has endured for so long that a new collection of short stories, Into the Forest (Black Spot Books), has came out and includes 23 different depictions of the figure written by top female horror authors. The tales span centuries, with Carina Bissett’s Water Like Broken Glass setting Baba Yaga against the backdrop of World War Two and Sara Tantlinger’s Of Moonlight and Moss providing a dreamlike recollection of one of the classic Baba Yaga tales, Vasilisa the Beautiful. While this is happening, EV Knight’s Stork Bites intensifies the myth’s horrible elements as a cautionary tale for curious kids.

The backstory of Yaga

The first written mention of Baba Yaga is from 1755 and is found in Mikhail V. Lomonosov’s book Russian Grammar as part of a discussion on Slavic folk figures. Baba Yaga is a prominent figure in many Slavic and particularly Russian folk tales. Prior to that, she had made frequent appearances in volumes of Russian folklore and woodcut art, dating back at least to the 17th Century.

If you enjoy watching movies, you might recognize the moniker from the Keanu Reeves-starred John Wick movies, in which the antagonistic Baba Yaga is referred to by his foes, giving him the attraction of a nearly mythical bogeyman. Legendary Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki based the owner of the bathhouse in his acclaimed 2001 film Spirited Away on Baba Yaga. Baba Yaga also occurs in music; the ninth movement of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition suite from 1874 is titled The Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba Yaga). Given that Neil Gaiman utilized her in his Sandman comics for DC, whose Netflix adaptation has received a second season order, she may also soon be seen on television.

Baba Yaga was also used by Gaiman in the comic book series The Books of Magic, and the way he employed the character shows her moral ambiguity: in contrast to Sandman, where she was helpful, Books of Magic portrays her more as a villain. He claims that when he was six or seven years old, he read Margaret Storey’s children’s fantasy novel The Dragon’s Sister and Timothy Travels, which featured Baba Yaga.“[I] felt she was the most interesting of all the witches, and felt that way even more when I read some of the Russian stories in which she appears,” he says. “She seems to have her own life outside of the story, which so few fairy tale characters do.”

The publisher of Into the Forest, Black Spot Books, a tiny company devoted to female horror authors, was founded by Lindy Ryan, a writer and full-time professor of data science and visual analytics at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Ryan also serves as the editor of Into the Forest. How, therefore, could an American become so enthralled by this Slavic legend?

“My Russian stepmother emigrated to the United States shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union,” says Ryan, “and along with my stepsister and step-babushka, she brought borscht, matryoshka dolls, and Baba Yaga. While most girls my age were growing up with nicely sanitised Disney version princesses, I preferred the stories by Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, and Hans Christian Andersen – and, of course, in the books of Slavic fairytale and folklore that talked of Baba Yaga.”

Baba Yaga’s origins may actually date back much earlier than the 17th century; according to one school of scholarly opinion, she is a Slavic analogue of the Greek goddess of spring and nature Persephone. She undoubtedly conjures up images of the wildness of nature, as well as trees and forests. “The essence of Baba Yaga exists in many cultures and many stories, and symbolises the unpredictable and untameable nature of the female spirit, of Mother Earth, and the relationship of women to the wild,” says Ryan.

Baba Yaga’s duality—at times portraying herself as an almost-heroine and at other times as a villain—and her deep, earthy portrayal of womanhood set her apart from the typical two-dimensional witches of folklore. “Baba Yaga still remains one of the most ambiguous, cunning, and clever women of folklore,” says Ryan.

A real outlaw

Izzy compares trickster figures like Coyote from Native American legend and the Norse deity of mischief Loki to Baba Yaga. “While Baba Yaga often plays a villain, she is also likely to offer assistance. For example, in Vasilisa the Beautiful, she helps free Vasilisa from the clutches of her evil stepfamily,” she says. “And while Baba’s dangerous to deal with, like many of those who operate on the shadowy side of the law in contemporary movies, she can as well prove herself invaluable in dangerous circumstances.

“In this way, Baba Yaga complicates the passive female nurturing role with a type of ‘I’ll do whatever the heck I want’ outlaw power that you ordinarily only see associated with men. You could say then that Baba Yaga crosses the wicked witch trope with the fairy godmother trope to create an ultimately far more unpredictable and powerful role than either of those.”

Izzy was born and raised in Northern China, and because to the extensive translation of Russian literature into Chinese, Baba Yaga made its way across the border and into Chinese culture. “My first exposure to Baba Yaga was a Chinese cartoon I saw when I was very young. I remember this cartoon because I told my grandmother that Baba Yaga looked exactly like my Big Uncle. This made her laugh. Big Uncle did not laugh,” says Izzy.

Izzy’s work, The Story of a House, recounts the building of one of the distinctive aspects of the Baba Yaga legend – her rickety cottage that walks on chicken legs. “I was just charmed thinking of the little chicken legs of this big old house. This directly led me to wanting to write something about the house. As well, I had just come off translating The Shadow Book of Ji Yun – a collection of 18th-Century Chinese weird tales. It’s filled with fox spirits, Tibetan Red-Hat black magic, and other flavours of shamanism, as well as stories of preternaturally intelligent or empowered animals and weird metamorphoses. This inspired the atmosphere I wanted to create in The Story of a House and its themes.”

Are there any timeless truths in the story of Baba Yaga? Izzy concurs. “She’s a shamanic trickster, a category and boundary-crosser, a [reminder] that freedom lies a little beyond the border of social norms, and that we can learn as much from the dark as the light. Ultimately, I think she teaches ‘Both/And’ logic. She reminds us that we are both hero and villain, that a chicken can also be a house, and that we can embrace both the desires of the flesh and the secrets of the spirit.”

Ryan concurs and issues a wise caution to those who would minimize Baba Yaga’s influence and, by extension, the influence of women everywhere. “I think we’d do best to remember that Baba Yaga may hide herself in the woods, but she is watching and she is remembering,” she says.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.