Depict Ukraine’s soul

When Russia took the Crimean peninsula in 2014, the Russian humorist Vladimir Sorokin wrote about how his friends reacted to the subsequent fighting. “I can’t believe that Russia and Ukraine are fighting. It’s like a nightmare,” said one. Another added: “All of us Russians are sitting in a huge theatre, watching a play called Ukraine. And you can’t leave the theatre!”.

As stunned and appalled as Sorokin and his pals, we are all now watching. Behind the news, though, is something more durable that serves as a portrait of Ukraine’s culture and its people. It is a site that has been extensively depicted in writings and stories for many years and continues to fascinate writers today due to its distinct geopolitical location and stormy history. BBC Culture set out to investigate Ukrainian literature’s history and interview authors who are most familiar with it.

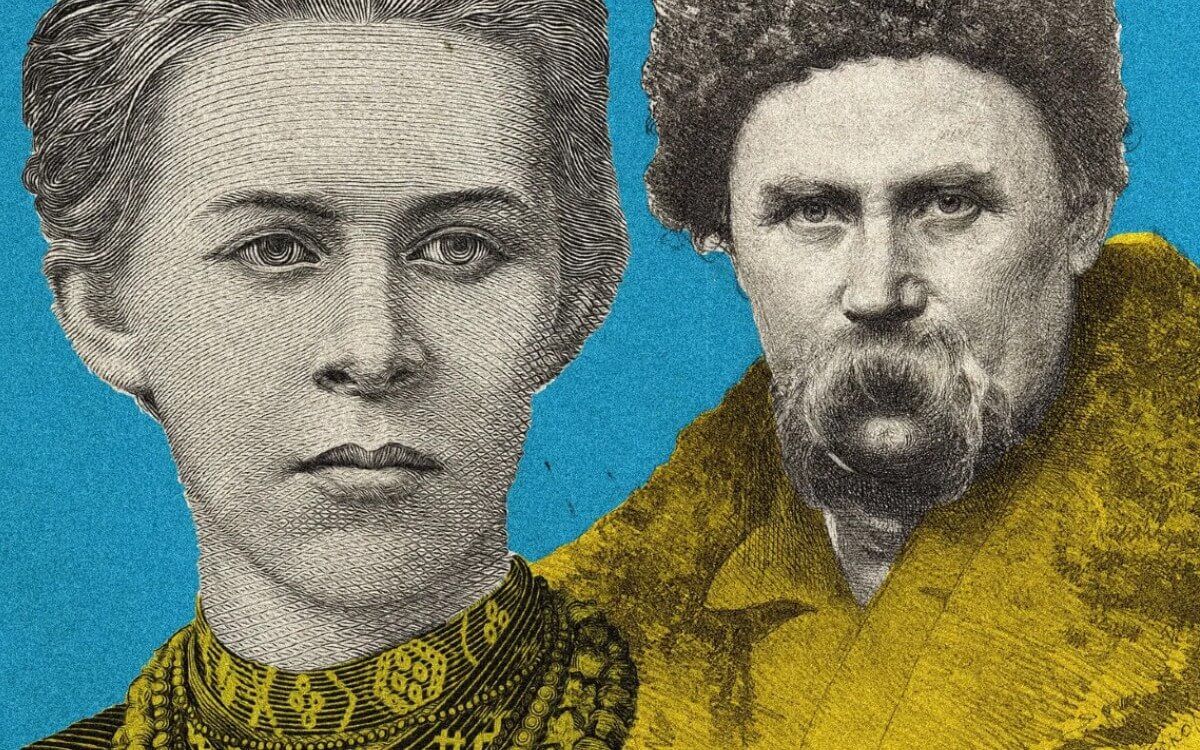

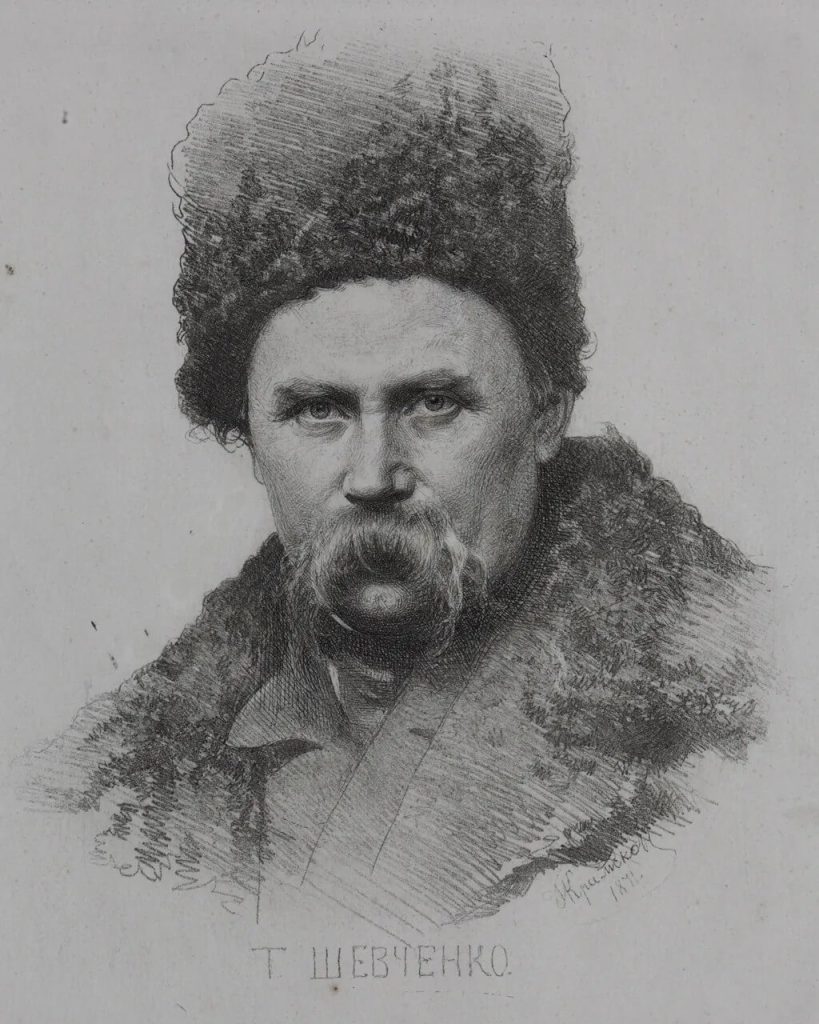

Ukrainian-born writer and translator Boris Dralyuk presently resides in the US. When asked about how Ukraine is portrayed in literature, he names Taras Shevchenko as one of its literary forefathers (1814-1861), “the national poet of Ukraine, a sort of Pushkin-like figure who was born into serfdom, whose talent bought him his freedom.” One of Shevchenko’s poems is A Cherry Orchard by the House (1847): “A tiny little lyric,” says Dralyuk. “It won’t strike you as brilliant poetry, but for Ukrainians, it’s the very image of home. It just lodges in your heart and you can’t shake it.”

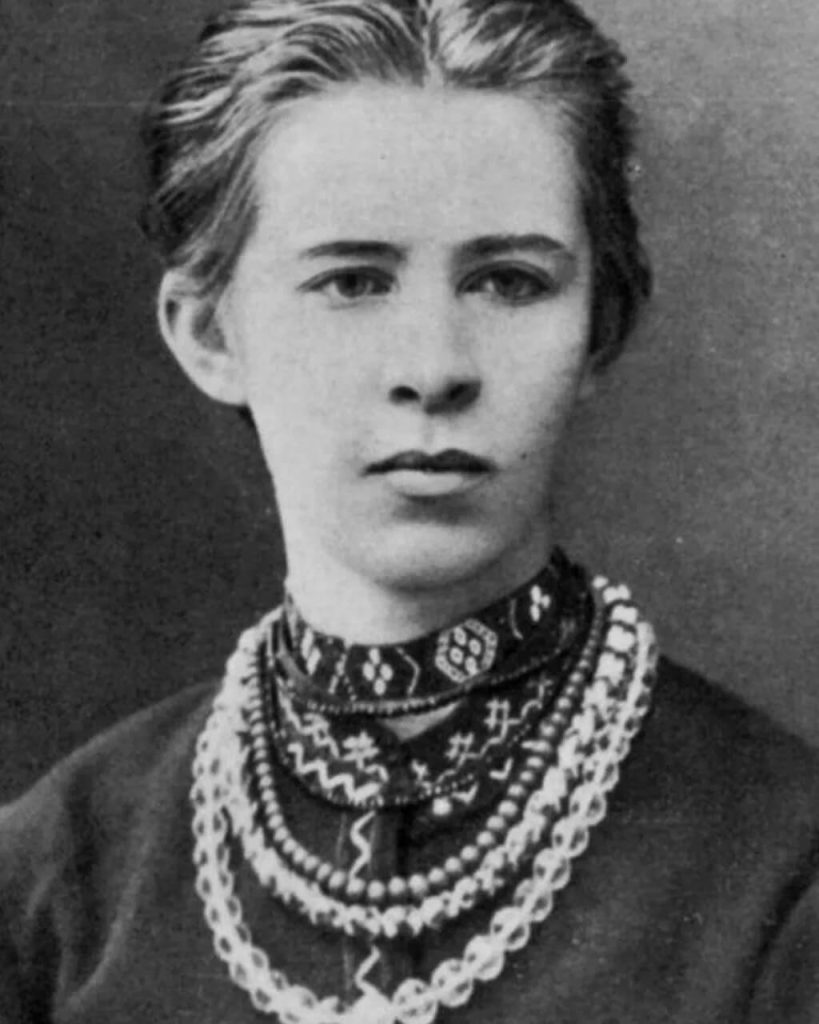

Lesya Ukrainka (1871–1913), a poet who was influenced by Shevchenko and was, in Dralyuk’s opinion, “a kind of proto-feminist figure [and] you can tell by her choice of pseudonym that she was very much, if not a nationalist then a patriot. Her image has been on Twitter frequently, because Ukrainian women have shown so much courage [recently], so she’s become a symbol of that kind of resistance.”

However, outside of Ukraine, neither Shevchenko nor Ukrainka are well known. It is unfortunate, though appropriate, that some of the most well-known early literary representations of Ukraine are by outsiders, particularly those that chronicle the Crimean War in the 1850s. Commentators called this battle between Russia and an alliance that included Britain and France a “boozy fiasco.”

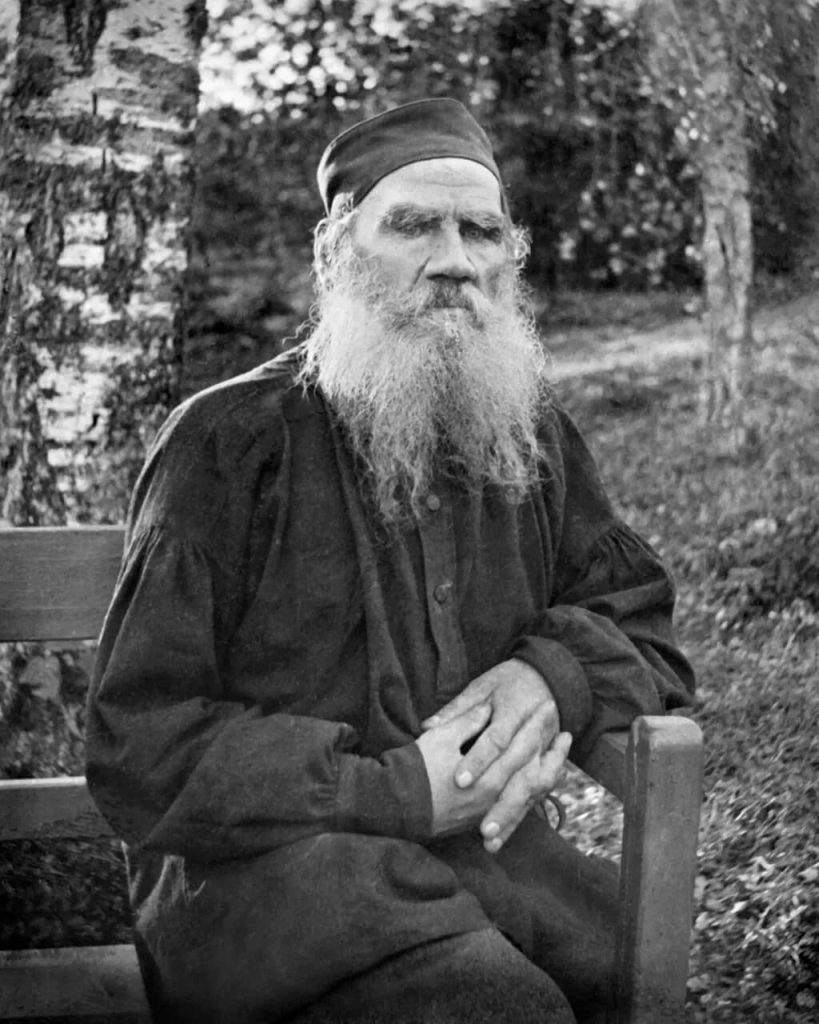

From the Russian side, the Crimean War produced arguably the first war journalist in history, Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy, a young officer in the Russian army with a passion for literature who reported on the siege of the port of Sevastopol in 1854-55. His three “Sevastopol sketches” exhibit Tolstoy’s traits in an early stage: an amalgamation of politics and characters, meticulous historical reconstruction, and a keen eye for larger-than-life characterization.

“Ukraine is a country with an innate sense of humility, a great sense of humour, and a very healthy self-regard” – Boris Dralyuk

The sketches read like fiction, full of life and death, but for Tolstoy “the hero of my story, whom I love with all my heart and soul,” was “the truth”. He didn’t care whether his sketches offended anyone – “all the characters are equally blameless and equally wicked” – and they made him into a literary celebrity. “I failed to become a general in the army,” he wrote, “but I became one in literature.”

The works of Tolstoy and Tennyson serve as illustrative instances of the pervasive notion of Ukraine as a nation not only devastated by battle but also divided. Historically, the area that is now known as Ukraine—a country that has only been independent for three decades—was a crossing point from the West to the East. West Ukraine belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the 19th century, while Russia dominated the east. It was briefly united as the Ukrainian People’s Republic at the beginning of the 20th century, but it was soon divided once more between Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Russia before joining the Soviet Union.

The city of Lviv in western Ukraine was formerly known as Lvov, Lwów, or Lemberg, depending on who was in authority at the time. This is one way to understand its turbulent history.

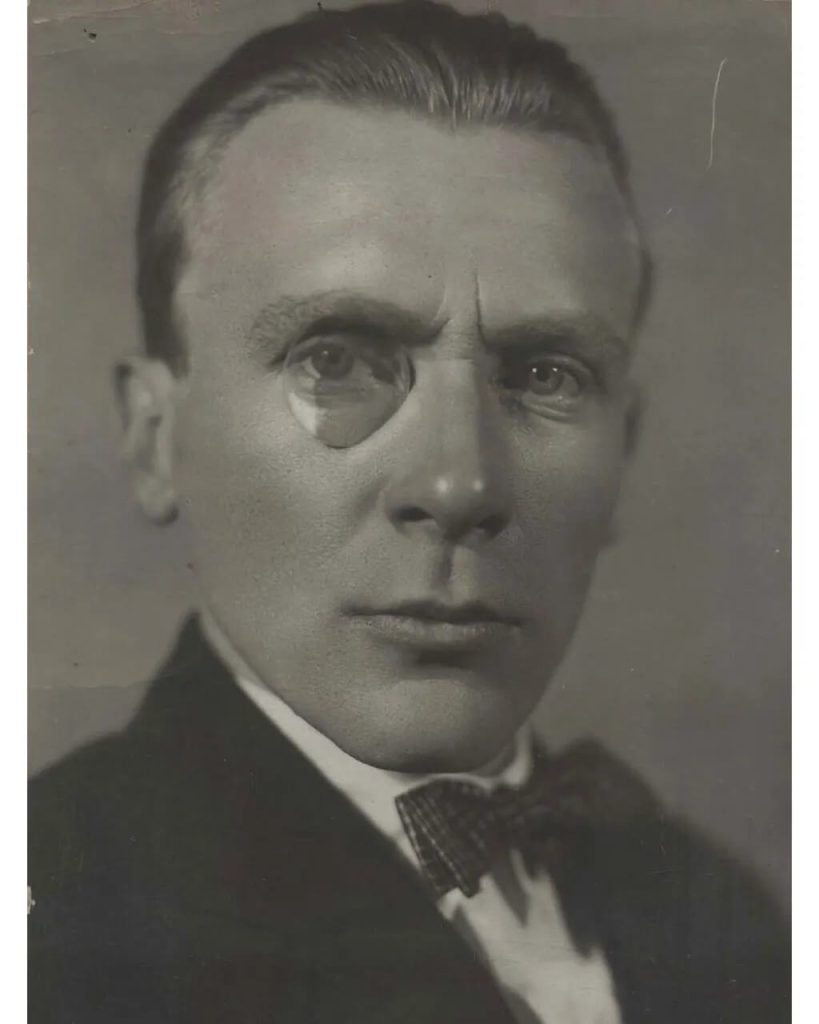

Another option is to take a cue from Ukrainian-born author and humorist Mikhail Bulgakov, who famously observed wryly that in his hometown of Kyiv in the years following 1918, “there were 14 [changes of power], of which 10 I personally experienced.” His first significant work, The White Guard (1925), which is set during one of those battles for control of Kyiv and chronicles the miseries of the once-rich Turbin family, is Bulgakov’s personal contribution to the literature of the Ukrainian conflict. (The book was banned by Soviet censors because it lacked a communist hero.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.